Portuguese colonizers first established São Tomé as a sugar producer in the 16th century, but by the late 1800s, the islands pivoted to cocoa. The volcanic soil proved perfect for cacao trees, and within decades, São Tomé and Príncipe dominated global chocolate production.

By 1905, these small islands produced more cocoa than anywhere else on Earth, supplying Europe’s growing appetite for chocolate. The British companies Cadbury, Rowntree, and Fry – household names that still exist today—all sourced their cocoa primarily from São Tomé.

What visitors see today: The massive roça plantations still dot the landscape. These self-contained estates functioned like small towns, complete with housing, processing facilities, and administrative buildings. Many are now atmospheric ruins you can explore, their colonial architecture slowly being reclaimed by rainforest.

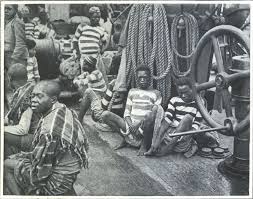

The history of São Tomé cocoa is inseparable from forced labor. While Portugal officially abolished slavery in 1878, the serviçal system that replaced it was slavery in all but name.

Workers were forcibly recruited from Angola’s interior, marched to the coast in shackles, and shipped to São Tomé. Once on the islands, they worked under contracts that theoretically allowed return home—but records show almost no one ever left. Between 1888 and 1908, an estimated 67,000 Africans were transported to these plantations.

The wealth generated by São Tomé cocoa was built entirely on this coerced labor system. Every chocolate bar produced by European manufacturers during this era was connected to this human cost.

The Quaker families who owned Britain’s major chocolate companies—particularly Cadbury—faced a moral crisis. Their religious beliefs emphasized social justice and abolition, yet their businesses depended on São Tomé cocoa.

When journalist Henry Nevinson published detailed accounts of the labor conditions in 1905-1906, the scandal erupted publicly. Cadbury attempted quiet diplomacy with Portuguese authorities, but change came slowly. By 1908, the Standard News newspaper accused Cadbury of knowingly using slave-produced cocoa.

The resulting libel trial became a landmark case. Cadbury won technically—the jury found the newspaper guilty of libel—but awarded damages of just one farthing (a quarter of a penny). This “contemptuous” amount was the jury’s way of saying: “You’re not lying, but you took far too long to act.”

In 1909, major European chocolate makers finally boycotted São Tomé cocoa, shifting their purchases to the British Gold Coast (now Ghana). This commercial pivot permanently changed the global cocoa trade and inadvertently made Ghana the chocolate powerhouse it remains today.

For visitors who want a deeper, primary source based account of Cadbury’s internal investigation and the campaign against São Tomé slavery between 1901 and 1908, the William A Cadbury Charitable Trust has an accessible narrative: The Campaign against Island Slavery 1901–1908

The São Tomé Roças are the soul of the islands, blending history, community, and the finest chocolate in the world. Are you ready to step into this extraordinary heritage?

The roças are among the most atmospheric historical sites you can visit in São Tomé and Príncipe. These sprawling estates offer a tangible connection to the islands’ complex past.

Roça Agostinho Neto (formerly Roça Porto Alegre) near Angolares is one of the most accessible, featuring impressive colonial architecture and processing buildings. You can walk through the former workers’ quarters and see the original cocoa drying platforms.

Roça São João dos Angolares has been partially restored and occasionally hosts cultural events, giving visitors insight into both the colonial era and contemporary Santomean life.

Roça Sundy on Príncipe Island, where Einstein’s theory of relativity was confirmed in 1919, combines scientific and colonial history. It’s now a boutique hotel, allowing overnight stays in restored plantation buildings.

Many roças remain abandoned, their walls covered in vines—haunting monuments to a painful chapter in history. Walking through these ruins, you’ll see massive processing equipment rusting in place and former administrative buildings with nature pushing through their walls.

Today’s São Tomé history isn’t just about confronting the past—it’s about transformation. The islands are rebuilding their cocoa industry on principles of organic farming and fair trade.

The CECAB cooperative (Cooperativa de Exportação de Cacau Biológico) supports smallholder farmers, particularly women, with organic certification and fair pricing. Farmers like Camila Varela De Carvalho work as inspectors and producers, ensuring quality while earning sustainable incomes for their families.

Unlike the massive colonial plantations, today’s cocoa production happens on small family farms. The focus is on quality over quantity, with São Tomé chocolate gaining recognition among artisan producers worldwide.

Experiences for visitors:

Plantation tours at working organic farms let you see cocoa cultivation from tree to finished product. You’ll taste beans at different processing stages and sample locally made chocolate.

Chocolate tastings feature São Tomé’s distinctive beans, which produce chocolate with unique fruity and floral notes.

Farm stays offer immersive experiences where you can participate in harvesting or processing during the main season (October-December and May-June).

These tourism activities directly support the ethical chocolate economy, providing income that helps farmers avoid exploitation.

The companies that built their empires partly on São Tomé cocoa still exist, though under different ownership:

Cadbury (now owned by Mondelez International) and Fry’s (merged into Cadbury) were the primary British buyers

Rowntree brands (now owned by Nestlé) sourced heavily from São Tomé until 1909

Stollwerck (now part of various confectionery companies) was the major German buyer

Modern corporate social responsibility standards demand far more than the reactive boycott of 1909. Today’s chocolate industry faces ongoing scrutiny over labor practices, particularly in West Africa, making São Tomé’s ethical production model increasingly valuable.

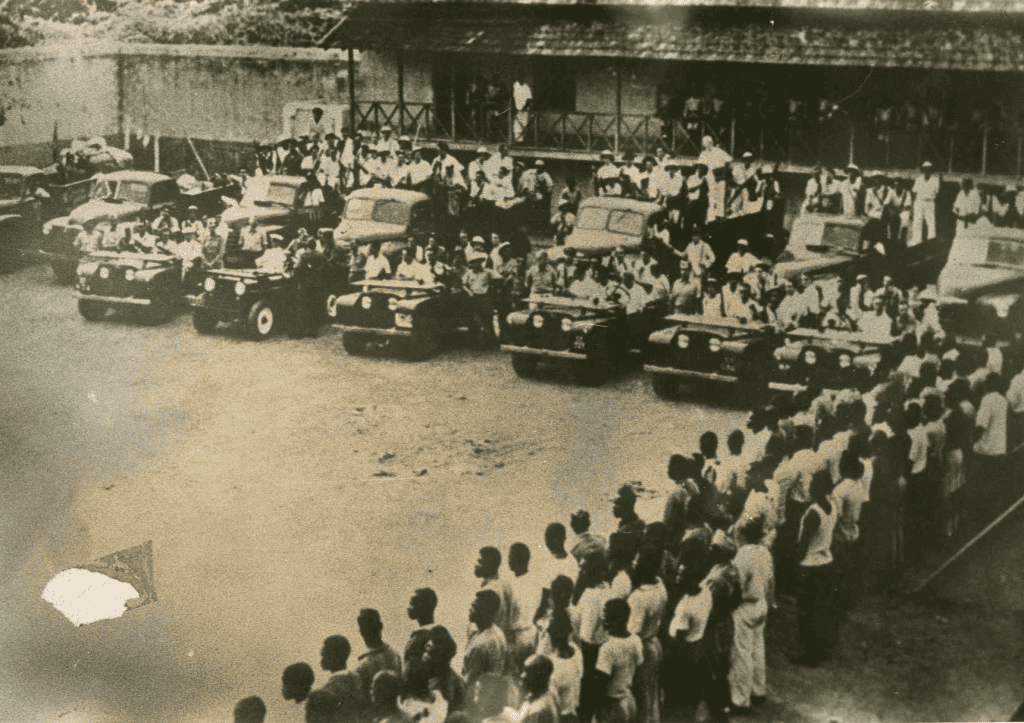

February 3rd is a solemn day in São Tomé and Príncipe. Known as Dia de Mártires da Liberdade (Day of Freedom Martyrs), it commemorates one of the darkest moments in the islands’ history—and the catalyst for independence.

The Batepá massacre of 1953, when hundreds of native Santomeans were killed by colonial authorities and Portuguese landowners, marks the moment when resistance transformed into a full independence movement. Understanding this event is essential to understanding modern São Tomé and Príncipe.

By the early 1950s, São Tomé remained one of the world’s largest cocoa producers. The massive plantation estates- the roças – still dominated the island’s landscape and economy, operated as quasi-feudal systems using contract laborers (serviçais) brought from mainland Africa and Cape Verde.

The native Santomean creoles, known as forros, had always refused to work in the plantation fields. They considered this manual labor to be slavery by another name—and their historical memory wasn’t wrong. The forros were descendants of freed slaves and had maintained their independence from the plantation system for generations.

Governor Carlos Gorgulho, who took office in 1945, wanted to change this. His economic modernization plans required breaking São Tomé’s dependence on imported contract labor. He implemented policies to make it easier for serviçais to return home while simultaneously trying to force forros into plantation work through economic pressure—banning palm wine sales, prohibiting locally produced gin, and tripling the poll tax from 30 to 90 escudos.

In 1952, the colonial administration proposed settling 15,000 people from Cape Verde on São Tomé. By January 1953, rumors spread throughout the forro communities that the government planned to seize their land for these new arrivals and force them into contract labor on the roças.

The fears were not unfounded. The colonial administration had been using police raids to kidnap people for forced labor gangs working on public construction projects. The memory of the 19th-century slave trade—which had ended only 75 years earlier—remained vivid in community memory.

On February 2, 1953, hand-written pamphlets appeared in São Tomé threatening to kill anyone who contracted forros as laborers.

The colonial government’s response escalated the crisis dramatically. Governor Gorgulho issued an official declaration claiming that “communists” were spreading rumors and ordered citizens to report such individuals to police. He called on all white colonists to arm themselves to protect their families and property from what he claimed was an imminent communist rebellion.

On February 3, police killed Manuel da Conceição Soares, a protestor in one of the crowds that had gathered. His death triggered a larger protest in Trindade the following day.

What happened next was systematic violence on a horrific scale. Militias formed quickly, drawing in Portuguese colonists, some Cape Verdians, and contract workers from Angola and Mozambique mobilized by plantation owners. Over the following days, these militias and colonial forces killed hundreds of forros.

The methods were brutal:

Governor Gorgulho reportedly advised authorities: “Throw this shit into the sea to avoid troubles.”

On March 4, Portuguese secret police (PIDE) arrived from Lisbon to investigate the alleged communist conspiracy. They quickly determined there was no such conspiracy. In April, the Minister of Overseas Territories ordered Gorgulho back to Lisbon.

Rather than face consequences, Gorgulho was promoted to general and praised by the Minister of the Army for his actions. Seven forros were tried and convicted for killing two police officers—the only colonial casualties. No investigation into the hundreds of murdered forros was ever conducted.

The exact death toll remains unknown. Conservative estimates suggest hundreds were killed, but the practice of disposing bodies at sea makes precise accounting impossible.

Today, visitors can pay respects at several sites connected to the massacre:

Fernão Dias Beach Memorial in São Tomé city features a monument erected in 2015 at the coordinates where many bodies were dumped into the sea. It’s a powerful reminder of the violence and a place where Santomeans gather each February 3rd for remembrance ceremonies.

Trindade is where the major protest occurred on February 4, 1953. The town remains an important site in Santomean historical memory.

On February 3rd each year, national commemorations take place throughout the islands. If you’re visiting during this time, attending the ceremonies offers profound insight into how Santomeans understand their national identity. The day is observed with solemnity—speeches, wreath-laying, and remembrance gatherings honor those who died.

Understanding the Batepá massacre adds crucial context to several aspects of your São Tomé visit:

The abandoned roças aren’t just picturesque ruins they’re monuments to a system that forros resisted so fiercely they were willing to die rather than submit. When you walk through places like Roça Agostinho Neto or other plantation estates, you’re seeing the physical structures that represented generations of exploitation.

Independence celebrations on July 12th carry special weight when you understand the path to freedom began with the massacre twenty-two years earlier.

Modern Santomean identity is deeply shaped by this history. The pride in small-scale, ethical cocoa production isn’t just about economics—it’s about forros and their descendants finally controlling their own agricultural destiny.

Racial dynamics in contemporary São Tomé reflect the complicated legacy of who participated in the massacre. The involvement of some Cape Verdian settlers and mobilized contract workers from Angola and Mozambique created tensions that took decades to heal.

The Batepá massacre is not ancient history. Many elderly Santomeans alive today had parents or grandparents who lived through 1953. Some lost family members. The trauma remains part of living memory.

For visitors, understanding this event transforms your experience of São Tomé and Príncipe. The emphasis on independence, dignity, and economic self-determination that you’ll encounter throughout the islands isn’t abstract—it’s rooted in this specific historical moment when hundreds died resisting forced labor.

When you support locally-owned tourism businesses, buy organic São Tomé chocolate from cooperatives like CECAB, or hire forro guides to show you the roças, you’re participating in the realization of what those murdered in 1953 were fighting for: Santomean control over Santomean resources.

This is painful history, and visitors should approach it with appropriate respect:

If attending February 3rd commemorations, dress respectfully and remain quiet during ceremonies.

The memorial and the annual commemorations are not tourist attractions in the conventional sense—they’re active sites of national mourning and identity. Visitors are welcome to observe and pay respects, but should do so with the gravity the history demands.

The arc of São Tomé history from 1953 to today tells a story of resilience. The massacre intended to terrorize forros into submission instead galvanized resistance that led to independence. That independence enabled Santomeans to rebuild their chocolate industry on ethical foundations.

When you visit São Tomé and Príncipe (and you should), you’re seeing a nation that fought for—and won—the right to determine its own future. The Batepá massacre stands as both a warning about colonial violence and a testament to the courage of those who refused to accept it.

Every February 3rd, São Tomé and Príncipe remembers. As a visitor, taking time to understand why adds depth and meaning to everything else you’ll experience on the Chocolate Islands.

Understanding this history enriches your visit to São Tomé and Príncipe in several ways:

Context for what you see: The impressive roça buildings, the distribution of settlements, even the mix of Portuguese and African influences- all reflect the plantation economy that shaped these islands.

Meaningful engagement: Buying organic São Tomé chocolate or visiting fair-trade farms isn’t just tourism – it’s participating in the islands’ attempt to rewrite their chocolate story on ethical terms.

Deeper appreciation: The transition from world’s largest producer to small-scale quality production explains why São Tomé feels different from other tropical destinations.

There’s an awareness here of trying to build something better.

The coerced labor system persisted until São Tomé and Príncipe gained independence in 1975—relatively recently in historical terms. Many elderly Santomeans remember the final years of Portuguese colonialism, and the roças are living memory, not ancient history.

Exploring São Tomé history works well as part of broader island tours. Most visitors combine:

Northern plantation tours featuring several accessible roças and the colonial capital São Tomé city

Central region visits including Monte Café, a high-altitude plantation still producing coffee and cocoa

Southern routes through the former plantation heartlands around Angolares

Consider hiring a local guide familiar with both the history and the specific stories of individual roças. Many guides have family connections to the plantations and can share personal narratives that bring the history alive.

The best time for cocoa-focused visits is during harvest seasons when you can see the full process in action. However, the roça ruins and chocolate tastings are year-round experiences.

São Tomé and Príncipe earned a nickname that sounds delicious but hides a darker past. Known as “the Chocolate Islands,” this tiny archipelago off West Africa’s coast became the world’s largest cocoa producer by 1905. Today, visitors to these lush islands walk through the remnants of that era—crumbling plantation estates called roças—while the country rebuilds its chocolate industry on ethical foundations.

Understanding São Tomé history means confronting its colonial past while appreciating how the islands are transforming that legacy into something visitors can experience and support today.

Need Advice?